I am on a Boeing 757, sitting in the economy section, one of the few times I am grateful for having short legs. I am returning home from New York where a film I conceived and executive produced just premiered at the Tribeca Film Festival. It is truly an honor, given the numbers: 6700 films were submitted and only 120 were selected for the competition. The film, “Autism in Love,” is in the “world documentary feature” category, competing against 11 others in its category for a coveted award.

I am on a Boeing 757, sitting in the economy section, one of the few times I am grateful for having short legs. I am returning home from New York where a film I conceived and executive produced just premiered at the Tribeca Film Festival. It is truly an honor, given the numbers: 6700 films were submitted and only 120 were selected for the competition. The film, “Autism in Love,” is in the “world documentary feature” category, competing against 11 others in its category for a coveted award.

One of the films in competition with “Autism in Love” is called “In Transit,” a beautiful and moving documentary interweaving stories told by real passengers (i.e., not actors) on the Empire Builder, an AMTRAK train whose route goes from Seattle to Chicago. The stories themselves are captivating, but I was equally captivated by the fact that the stories were told as the American landscape unwound behind it, creating a kind of metaphor within a metaphor. Each person seems to be in some sort of transition in their lives, moving internally as they physically move through the landscape. But on a train, the sensation is that it is the landscape that is moving, so that one’s internal movement is mirrored by the movement of the landscape. And of course, all that occurs on a screen projecting a “moving picture,” a medium that is, by definition, about movement.

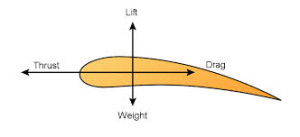

I am doing the same thing now, traveling at 514 miles per hour, four-fifths the speed of sound, 40,000 feet above the ground. We humans, through the ingenuity provided by our cerebral cortexes, create and build machines that allow us to use nature in order to defy it. We build machines that move us from one place to another for many reasons, but ultimately we build machines that move us physically in order to move us emotionally.

The film I produced, expertly directed by Matt Fuller, follows the lives of several people diagnosed with autism as they navigate the waters of romance and love. Their lives are very different from one another’s, but they each live in the landscape others have called autism. I have lost any objectivity I might have had about the film, but judging by the reviews I have been reading, it succeeds in a message I was hoping for; that love is love and nearly anyone, despite having a label that others insist prevent them from loving, can teach us about it.

In college days I was taught that humans, by nature and physiology, are novelty seeking animals. That is undoubtedly what makes solitary confinement so punishing. But without the contrast of stability there could be no novelty, just as a figure disappears when the ground around it disappears.

So whether we find ourselves riding the rails of AMTRAK, sitting on a bus, or flying on a Boeing 757, we ultimately remain figures embedded in the world around us. We are moving, or being moved.

For more information on “Autism in Love,” see www.autisminlove.com, or better yet, see “Autism in Love” on Facebook.