There is a scene in the recent movie, “The Way, Way Back” in which the 14-year-old lead character discovers a bicycle in the garage of his mother’s new boyfriend’s summer cottage where he has been trapped for what promises to be a torturous summer. With a spectacular blast of background music he breaks out of the garage on the diminutive bike and rides away with a new sense of freedom.

There is a scene in the recent movie, “The Way, Way Back” in which the 14-year-old lead character discovers a bicycle in the garage of his mother’s new boyfriend’s summer cottage where he has been trapped for what promises to be a torturous summer. With a spectacular blast of background music he breaks out of the garage on the diminutive bike and rides away with a new sense of freedom.

The scene struck a deep chord for me, because it brought back memories of my childhood, when, each day after school in order to escape the constant shouting and threatening in my family, I would ride as far away as I could on my bike until I became just a bit lost, and then eventually find my way home. I remember never really wanting to go home, and trying to calculate ways to run away, but as a young child I of course didn’t have the wherewithal.

I remember the sense of freedom I had when riding my bike, the sense of movement and the rush of air over my face, and even a more acute sense of smell. When I left Queens at age 10 my family moved to Framingham, Massachusetts, where we lived on a suburban street on a small hill. At that age the hill wasn’t so small, and I distinctly remember getting on my bike at the top of the hill, raising both hands in the air, and closing my eyes as the bike picked up speed on the way down. I could even turn the corner at the bottom of the hill with no hands and no sight, just the sensation of the bike beneath me and the air blowing over my chest and face.

That thrill ended when one day I took the turn at the bottom of the hill and hit a parked car. I was thrown first into the handles, which knocked the wind out of me, then tossed onto the trunk of the car to be stopped by the rear window. The car was dented, and I was bruised, but nothing else broke. That was probably my first memory of flying, albeit without wings.

In high school in California I learned to drive, and that became the E-ticket to freedom. Driving up the winding Pacific Coast Highway on a chilly night, windows open, music blaring, the heater throwing warm air at my feet; this was the closest thing to ecstasy a 16-year-old virgin could experience. I worked odd jobs during high school just to pay for gas and I would drive my ‘65 Barracuda as far as I could in any direction until the gas was half gone, then turn around and see if I could make it home before I ran out.

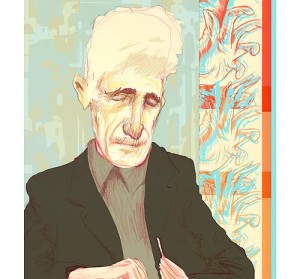

Whenever I am stopped on the street by a stranger and asked what my favorite poem is, I tell them it is this one by Mark Strand:

In a field

I am the absence

of field.

This is

always the case.

Wherever I am

I am what is missing.

When I walk

I part the air

and always

the air moves in

to fill the spaces

where my body’s been.

We all have reasons

for moving.

I move

to keep things whole.