Although it’s only flown once in the last year, my airplane is still required to undergo its (expensive) annual checkup, because in this country of fractured health care and inconsistent legislative imperatives, we are required to take better care of our airplanes than we are of ourselves.

While it is receiving its annual checkup, it is taken apart and I cannot fly it. But I miss her, so after writing this, and going shopping for dinner tonight, I will be heading to my hangar to pay her a short visit. I know it can get cold and lonely in that hangar, especially with the cowling off.

It is said that absence makes the heart grow fonder, which is a platitude that has always rung true for me, at least until enough time passes that the walls of the heart thicken and whatever fondness may have resided there calcifies just enough to cause the heart to stop beating and kill us. That is why falling in love with anything or anyone is one of the worst ideas God has implanted in the human psyche, yet many of us weaklings do it anyway, over and over again, until we drop dead from grief and longing.

This is a problem with flying. If you love it, and can’t do it, it becomes oddly reminiscent of that feeling you had when you fell in love with the girl in fourth grade who didn’t know– and probably would never know until 45 years later when you’re married and connect for the first time on Facebook, that you even existed.

Not flying, as is true with unrequited love, presents the practical problem of what to do and how to handle oneself until the desperation ends and the steed once again becomes mountable. Many of us pass much of our time in this purgatory, and face the continual task of combatting the angst that sometimes accompanies languor. The challenge, it seems, is to somehow get comfortable with the emptiness, how to find value not only in what we do, but what we don’t do.

This, I have discovered, can be learned. I am a person who, when seeing an empty shelf in a bookcase feels compelled to find enough books to fill it up, or, when seeing a bare wall in my house, feels compelled to find a piece of art to make it interesting. These things and others like them is a kind of sickness, I think, a form of avoidance of the essential, the abstract, the quiet and pedestrian.

One of my earliest failed attempts at fiction was a story about a man staring at a bare plaster wall, noticing all the cracks in the wall, and wandering through the cracks as though it were a map leading him somewhere. The story, which sounds better as I describe it than what it was, was an unintended metaphor, I suppose, for how one can get lost in the mist of finding something in nothing, which, I suppose as well, is another metaphor for this life itself.

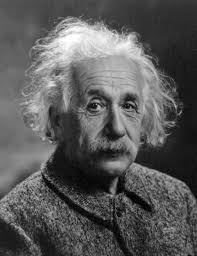

Ultimately, everything we either choose or are forced not to do presents us with an opportunity to do, learn, or be something else, and that reduces down to an attitude shift. Albert Ellis, one of the two major originators of cognitive-behavioral therapy, dubbed a certain kind of thinking musturbating, in which we get fixed on what we believe we must be doing, thinking, or feeling. Sometimes we think inside little boxes of our own creation, just like some of us manage to dress in the same drab style every day, not because it is what we particularly want to do, but simply because we feel skittish about stepping outside of our own boxes.

The voyeur in me loves to watch what people do when they are waiting to do something else. Pilots in pilot lounges are often diligently sitting at a computer screen checking the weather and planning their next flight, catching some z’s, watching a big-screen TV, or reading a newspaper. For some reason, I don’t see too many of them reading books, but that’s fodder for another post. At airports, as is true throughout the world, these days people are increasingly spending their precious time staring at their smart phone screens, probably, I assume, watching documentaries or studying the latest thoracic surgery research. I won’t tell you how I feel about “screen time,” although you can probably guess pretty well by now, but isn’t it sweetly hypocritical of me in that most likely you are reading this right now on some screen somewhere, and not in some tangible book, the pages of which you can feel and smell and put on a shelf and never have to worry about its batteries dying on you mid-sentence.

So I won’t be flying today, which, unto itself, is one of the several sad facts I am likely to encounter before the day is over. I do hate supermarkets, and I will be in and out in as short a time as possible. My challenge is how to make those empty spaces precious, how to find the maps to far-off places in the cracks in the otherwise bare walls, and I am confident that although I can musturbate at times with best of them, I am going to succeed.