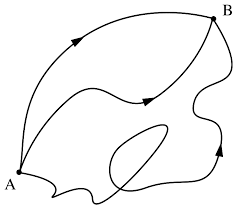

I have often been accused of being too literal, and so please understand that when I use the phrase “dumb luck” I have no intention of insulting anyone, but instead I use the phrase because, quite literally, luck itself cannot speak. It has no message, no meaning. It doesn’t know where it comes from and it doesn’t know where it’s going. It’s a meandering ghost lurking behind every tree and under every stone and in every breath we take and even those we don’t.

Pilots like to believe that they are in control of their destiny. It’s important that they believe that, because if they didn’t, they likely wouldn’t step foot in a cockpit and advance the throttle. Flying is certainly more dangerous than staying at home and watching TV, and that is because there are more opportunities for something unlucky to happen. “Fate is the Hunter” could not be a more apt title for aviation writer Earnest Gann’s autobiography, along with a 1964 film starring Glenn Ford and Suzanne Pleshette. Shakespeare said it best when, no doubt while sitting on a pubstool, he said, “Shit happens.” Good thing there was a bumper sticker writer around to write it down at the time.

I have found it fascinating over the years to listen to pilots discuss a recent deadly accident—any recent accident. One might think they would be kinder to fellow pilots, but most often they are angry and critical of the pilot who died. Even before knowing a detailed explanation, they blame the pilot for doing something stupid to cause their own demise. “Pilot error” is in fact the cause of over 75% of fatal accidents according to the NTSB, but there’s a big percentage left over. And that’s where the hunter comes in.

Dumb luck wields its unwitting existential sword in all directions. It kills and it rescues. Take, for example, my bout with stage IV cancer. I don’t exactly feel lucky to have survived this far, now seven years after my cancer diagnosis. Instead, I attribute my survival primarily to modern science and the physicians who have mastered their art at City of Hope. I never had much hope, really, nor did I have much faith. What I did have in copious amounts was resignation and compliance. And in the end, I think it was entirely them, the physicians, who were to blame for you reading these words. I am deeply grateful, even if you’re not.

But that too involved not a small measure of luck. I had a protein, labeled simply P16, residing in my squamous cell carcinoma that was particularly responsive to the chemotherapy and radiation that killed, or at least postponed, the tumor’s metastasis. That was lucky. And I was lucky to have found that team of physicians who practiced their art form flawlessly, as well as a profoundly supportive family to monitor and shield me from contextual harm.

And yet, there are those whose bodies end up downstairs, in the basement morgue, refrigerated until claimed by their loving and supportive families. Many of those had copious measures of hope and many of those even had sublime faith, but the mortality police came and snatched them anyway.

The thing about dumb luck is that, by definition, it is out of our control. We can hope and faith our way through the vicissitudes of this churlish life all we want, and the freaking plane might still crash, and the wayward car might run the light and smash us to smithereens. These are hard realities, and not incidentally, it’s the anticipation of the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune that is the definition of anxiety and the chief reason why pharmaceutical companies remain a good investment.

What remains out of our control can plague and preoccupy us, or we can choose the path of optimism, with the caveat that optimism when blind becomes ignorance, and ignorance causes a lack of the kind of healthy vigilance that keeps us relatively safe. Going with the flow I sometimes think can be fun in a kayak, but it can also smash the kayak into a boulder and ruin our day.

Optimism, I suppose, is simply the idea that luck strikes disproportionately on the positive side of things, giving more than it takes. The balance of probability, as Conan Doyle’s Holmes would say, certainly leans in that direction. Plane crashes happen every day, but proportionately to miles flown, that’s still very little. When they do, it’s usually the pilot’s fault, but usually isn’t always, and there’s still more than a smidgeon of fate involved. So, to paraphrase the brilliant folk musician Phil Ochs paraphrasing everyone else, there but for dumb luck go you or I.