In 1978, as United Airlines flight 173 was approaching the airport in Portland, Oregon, the captain noticed an abnormally loud thumping sound, along with an unexpected vibration and a yawing motion to the right. The captain aborted the approach and began to circle the airport while trying to solve the problem. Steeped in thought, he circled the airport for an hour, just long enough for all the fuel on board to be exhausted. The first officer casually mentioned the low-fuel condition to the captain, but the captain was too entrenched in problem-solving mode to heed the warning.

In 1978, as United Airlines flight 173 was approaching the airport in Portland, Oregon, the captain noticed an abnormally loud thumping sound, along with an unexpected vibration and a yawing motion to the right. The captain aborted the approach and began to circle the airport while trying to solve the problem. Steeped in thought, he circled the airport for an hour, just long enough for all the fuel on board to be exhausted. The first officer casually mentioned the low-fuel condition to the captain, but the captain was too entrenched in problem-solving mode to heed the warning.

The “good news” was that only 10 of the 189 people aboard died from the resulting crash because the lack of fuel on board prevented a fire on impact. And as a result of the accident new recommendations were put into place that led to what is now called crew resource management. This is a set of procedures pertaining to how members of the crew are to relate to one another in order to prevent confusion. One of these procedures has come to be called the “sterile cockpit rule,” in which no idle chatting is permitted below 10,000 feet (i.e., on takeoff and landing). Another pertains to the importance of speaking up assertively in the face of authority until a problem is resolved.

When I ran my own company I encouraged my employees to reveal to me any inadequacies they saw in the company. One of my supervisors sent me an email in which she outlined, in detail, all the things she thought was wrong with the company. When I received the email, I called to thank her and ask her permission to share her email with the other supervisors. I heard her take a deep breath, after which she said that she thought my phone call was going to be her termination notice. I told her that I admired her courage, and that I wanted to not only address her concerns, but to encourage other supervisors to emulate her.

Before I ran my own company, I worked for two non-profit mental health centers. In both places, I climbed the executive ladder quickly, moving from therapist to assistant clinical director at one agency in a matter of two years, “climbing” over others who were in some cases twice my age. Even in those days, I knew the “trick” was to meet with the people running the show, and respectfully tell them how they could do their jobs better. Though I knew I could be fired because they thought I was an egotistical upstart or gunning for their job, I had the good fortune of working for leaders who were not intimidated and did what James Collins (in the classic management tome “Good to Great”) saw as a hallmark of a great company– actively breed and nurture leaders who would ultimately take their pace.

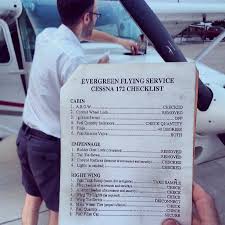

In my private pilot checkride,–the crucible that determines whether or not you earn your ticket to fly, there were three instances in which the examiner raised his eyebrows because I made decisions that were contrary to his expectations, but proved to be in the best interest of safety. Technically, the student on a checkride is acting as “pilot in command,” but most students emphasize the “acting” and will defer decisions to the examiner, who has the authority to determine your future ability to fly. It turns out that I made a lot of mistakes during my checkride, and was fully expecting to fail, but when the examiner told me I had passed I looked at him nonplussed, and he said to me, “You earned it.” I suspect it had a lot to do with the decisions I made to unabashedly yet humbly defy his preferences.

Several major aviation catastrophes later, a lack of standing up to authority has been cited as a potentially critical link in the accident chain. Without a doubt, leaders need followers in order to lead, but the best leaders know that the best followers are the ones who can be counted on to speak up, even at the risk of being punished for doing so.