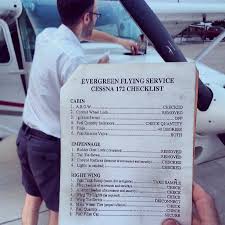

I made a few mistakes when taking my private pilot checkride, that crucible that determines whether or not you get the privilege of taking to the skies and risking life and limb. After showing the examiner that I could find my way from point A to point B without getting too lost, and that I could make the airplane go up and down, handle a loss of power and a few other tricks, he asked me where I wanted to “do my landings.” At that moment, we were flying almost directly over the town of Santa Paula, with an airport conveniently right below us. I told him I wanted to do my landings in Oxnard, some 13 miles away, which was one of several surprises I had for the examiner that day, because he was expecting that I would choose the airport right below us.

I made a few mistakes when taking my private pilot checkride, that crucible that determines whether or not you get the privilege of taking to the skies and risking life and limb. After showing the examiner that I could find my way from point A to point B without getting too lost, and that I could make the airplane go up and down, handle a loss of power and a few other tricks, he asked me where I wanted to “do my landings.” At that moment, we were flying almost directly over the town of Santa Paula, with an airport conveniently right below us. I told him I wanted to do my landings in Oxnard, some 13 miles away, which was one of several surprises I had for the examiner that day, because he was expecting that I would choose the airport right below us.

I chose Oxnard because it had once been a military base and the runways were long and wide, and really hard to miss. My checkride hadn’t been going so well up to then, and I wanted to give myself plenty of room for error, and landing in Santa Paula, even though I had already done it often, was like squeezing into the proverbial sardine can.

I had also landed in Oxnard many times, and each time I did my instructor had me begin my descent into that airport at just about where I happened to be at the time the examiner asked me where I wanted to do my landings, 13 miles away over Santa Paula.

As I began to descend, the examiner urgently asked me what I was doing. I was obviously doing something wrong; I just didn’t know what it was. I responded that I was beginning my descent into Oxnard. He impatiently growled at me something I have heard many times since then: “Remember– altitude is your friend.” He told me to climb back to my previous altitude, and not to descend into Oxnard until I absolutely had to. “You’re safer up higher. Down lower is where helicopters hang out. You’re in an airplane.” I’m not sure about my memory here, but I think I also heard him mutter, “For god’s sake, you’re not a crop duster.”

Of course the examiner was correct, and I have always tried to remember the phrase that “altitude is your friend.” Altitude keeps you safe because it gives you more time to figure out what to do if an engine quits, and more time to maneuver to a safe landing spot. But also, there are far fewer things to bump into the higher you go. “Controlled flight into terrain,” as it is officially called, is one of the biggest killers of pilots and their flying companions. Another reason we like altitude is that the higher you go the more you see, and it is therefore more difficult to get lost. Pilots learn “the three C’s” of what to do if lost while flying are to confess, climb, and communicate. You climb in order to be able to see more of what is around you.

Good management, whether it concerns an airplane, a business or one’s self, has a lot to do with the dance between immersion in the details (descending, if you will) and pulling up (climbing) to see the big picture. If, after all, the devil is in the details, perhaps the sky is where the angels reside.

It is not a matter of whether managing details or seeing the big picture is the best approach, but the ability to move between them that is important. Getting stuck in either the details or the big picture can be a recipe for disaster. In companies, it is often the CFO who is charged with mastering the details, while the CEO is typically the big picture person, but someone needs to make the final call, and that person is usually the CEO. It is too easy to miss the forest for the trees, and the best way to see the forest is from high above it.

Brandy Lovely, a Unitarian minister in Pasadena, used to tell a story about an argument he and his wife had over a small detail. He knew he was right, but the argument went on and on for hours as each of them dug their heels in. Finally, his wife said to him, “Look, do you want to be right, or do you want to be married?” Sometimes the big picture has to be forced upon us, and as my examiner reminded me, finding a way above it all can be our best friend.